This was written for a class in my program called, “Political Economics.”

Abstract

This paper investigates the impact of ‘Muslim-ness’ on gender attitudes. Using a cross-country analysis with Ordinary Least Squares and Instrumental Variables specifications – where Geographic Inequality and Distance from Pre-Islamic Trade Routes are used as instruments – I find a statistically significantly negative relationship between a nation’s ‘Muslim-ness’ and its overall gender attitudes. At a more granular scale, on average, an increase in the ‘Muslim-ness’ of a country is associated with lower female labor force participation, and more gender unequal attitudes on working women, women in politics, women as business executives and women in university education. I propose several potential policy options that may ameliorate gender inequality in these societies.

The Impact of Islam on Gender Attitudes: A Cross-Country Examination

“If any do deeds of righteousness be they male or female and have faith, they will enter Heaven, and not the least injustice will be done to them.” Al-Quran, 4:124

“And call to witness, from among your men, two witnesses. And if two men not be found then a man and two women.” Al-Quran, 2:282

I. Introduction

This paper examines the impact of Islam on gender attitudes. Specifically, it asks, “What gender attitudes prevail in countries which are historically ‘more Islamic’?” The paper attempts to answer the question via a cross-country analysis of contemporary attitudes towards gender equality (or inequality) in countries versus the degree of ‘Muslim-ness’ of those respective countries. I find that nations with a higher degree of ‘Muslim-ness’ are statistically significantly more likely to have more gender unequal attitudes. They are also more likely to have lower female labor force participation, and more gender unequal attitudes on working women, women in politics, women as business executives and women in university education.

The notion that religion can have important effects on social, economic and political outcomes has historically been one of deep interest, as evidenced by pioneering work by Max Weber (1905) who argued that Protestant societies were more likely to experience better economic outcomes because the Protestant ethic was embodied among the people in those societies. While this formulation has been challenged, for instance, by Becker and Woessmann (2009) who argue that it was rather the human capital channel – where Protestants had to learn to be literate as they had to learn to read the Bible – that led to more prosperous economies, the general sentiment still holds – religion, or aspects pertaining to religion, can lead to important social, political and economic outcomes. For instance, Barro and McCleary (2006) provide a helpful overview of the two-way relationship between religion and economic growth. This is corroborated by Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales (2003) who find that, on average, religious beliefs are associated with economic attitudes that are conducive to higher per capita income and growth.

Determinants of gender inequality are also widely explored. Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013) document that the historical use of plough technology in agriculture for a given society has negative effects on gender attitudes in present day for that society. Goldin (2006) discusses a ‘quiet revolution’ in American gender-labor history whereby the economic role of women was revolutionized in the 1970s as more women changed from static decision-making with limited horizons regarding their ‘jobs’ to dynamic decision-making with long-term horizons regarding their ‘careers.’ Bailey (2006) adds to this view by arguing that legal access to birth control pills in 1960 – thereby enabling women to plan childbearing and their careers – significantly reduced the likelihood of a first child before age 22, thereby increasing women labor force participation and the quantity of time worked. Albanesi and Olivetti (2007) posit that improvements in medical knowledge, obstetric practices and infant formula (technological progress) enabled married women to increase their labor force participation and thus, invest in their own human capital, potentially reducing gender wage gaps. Religiosity also matters. Morgan (1987) examined variation over a range of gender-role attitudes held by women and find that religious devoutness was the most important variable in predicting gender-role attitudes. Further, Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales (2003) find that religious people tend to be exhibit less favorable attitudes with respect to working women.

Linking Islam and gender inequality together and thereby establishing the key concern of this paper is the role of Islam on gender attitudes. Ross (2008) argues that while women have made “less progress” in gender inequality in the mostly Islamic Middle East compared to anywhere else, it is not Islam that is the problem, but rather oil production. Ross suggests that oil production is heavily biased against women vis-à-vis labor and thus, societies with heavy oil production are left with atypically strong patriarchal norms, laws and institutions. Ghazal Read (2003) studies the impact of religion on gender role attitudes among Arab-American women, among whom comprise Christians and Muslims, and finds that religiosity and ethnicity are more important in shaping gender role attitudes than are affiliations as Muslims or Christians.

On the other hand, while those papers provide arguments against the direct impact of Islam on gender attitudes, there is also good reason to hypothesize that Islam can lead to significant effects on gender attitudes. For one, the various de jure and de facto laws and norms from Muslim countries around the globe that discriminate against women may be a consequence of the ‘Muslim-ness’ of those nations. Furthermore, Campante and Yanagizawa-Drott (2013) find that while the practice of fasting during Ramadan, an important component of the practice of Islam, leads to lower output growth for Muslim nations, it also leads to an increase in subjective wellbeing among Muslims, namely overall happiness. If Islam may lead to particular subjective wellbeing outcomes among Muslims, it is not a stretch to reason that it may lead to particular gender attitude outcomes as well.

In addition, there is a sizable amount of work that links cultural norms and beliefs as important factors that explain persistent differences in gender roles across societies. Studies of this sort include Alesina and Giuliano (2010) which examines the role of the strength of family ties in shaping economic behavior and attitudes, Fernandez (2007) who reports that female labor force participation and attitudes in a women’s country of ancestry have quantitatively significant effects on women’s work outcomes in second-generation American women, Fernandez and Fogli (2009) which shows that cultural attributes have significant explanatory power on the work and fertility behavior of second-generation American women even after controlling for education and spousal characteristics and Fortin (2005) who investigates the impact of gender role attitudes and work values on women’s labor market outcomes across 25 OECD countries.

Defining culture, as per Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales (2006), as “those customary beliefs and values that ethnic, religious, and social groups transmit fairly unchanged from generation to generation,” and if we treat Islam as a part of culture, a longer history of Islam for a given country implies a longer transmission, unchanged from generation to generation, of customary beliefs and values on gender attitudes in that country. Thus, we can ask, “Do countries which are more Islamic have more negative gender attitudes or stereotypes?” Specifically, if we observe, for a given society, a higher degree of ‘Muslim-ness’ of the population, can we also argue that gender attitudes are more negative in that given society? Within the literature, there has hitherto not been any analysis on the impact of ‘Muslim-ness’ on gender attitudes and thus, this paper is a first attempt to fill that gap by asking, “What gender attitudes prevail in the present in countries which are historically ‘more Islamic’?”

This paper employs a cross-country analysis of ‘Muslim-ness’ on gender attitudes. The first order analysis is done by regular Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regressions, with a set of historical and contemporary controls, and continent dummies. For robustness checks for the OLS regressions, I vary the dependent variable based on different survey questions pertaining to gender attitudes taken from the World Values Survey wave of 2010 to 2014. The second order analysis is to delve deeper into identification and establishing causation. For this, I undertake an Instrumental Variables (IV) analysis with two instruments proposed by Michalapoulos, Naghavi and Prarolo (2012). The first is geographic inequality and the second is distance from pre-Islamic historical trade routes. The instruments are used to predict the Muslim-ness of a nation. I then regress gender attitudes against the nations’ predicted Muslim-ness. I replicate the this two-stage least squares regression for the other alternative dependent variables, for robustness checks.

I find a statistically significantly negative relationship between the ‘Muslim-ness’ of a country and gender attitudes in that respective country. In particular, a 10 percentage point increase in the Muslim-ness of a country is associated with, on average, a 0.07 point decrease in a gender attitude composite index, controlling for historical and contemporary controls, and continent dummies. To make it more concrete, the difference in gender attitudes that is attributable to the degree of ‘Muslim-ness’ of a society, on a 10 point scale, between Turkey and the United States, for example, is approximately 0.7 points, which is fairly substantial in practical terms.

At a more granular scale, on average, an increase in the ‘Muslim-ness’ of a country is associated with lower female labor force participation, a higher likelihood to hold the belief that men should have more right to a job than women when jobs are scarce, a higher likelihood to hold the belief that if a woman earns more money than her husband, it’s almost certain to cause problems, a higher likelihood to hold the belief that when a mother works for pay, the children suffer, a higher likelihood to hold the belief that, on the whole, men make better political leaders and business executives than women do and a higher likelihood to hold the belief that a university education is more important for a boy than a girl.

From a more general perspective, this paper and its results seek to contribute to the literature on how the historical persistence of culture can impact important social, political and economic outcomes today. This is in line with work by Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013), Alesina and La Ferrara (2005), Alesina and Fuchs-Schuendeln (2007), Roland and Tirole (2006), Bisin and Verdier (2000), Greif (2006), Tabellini (2008), Nunn and Wantchekon (2011), Nunn and Giuliano (2013), Nunn (2008, 2009 and 2012), among others.

This paper is organized as follows. Section II discusses the data and methodology used for the empirical analysis. Section III presents the results, both from the OLS estimations and the Instrumental Variable estimations. Section IV discusses the implications of the results and some potential policy recommendations. Section V concludes.

II. Data and Methodology

The key data of interest for this study is taken from the 2010-2014 Wave (Wave 6) of the World Values Survey (“WVS”) and the Correlates of War World Religion Project. Data for control variables on culture are taken from Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013), of which cross-country data for historical factors that may impact culture are posted online by Nathan Nunn. Data on the instruments, namely geographic agricultural inequality and distance from pre-Islamic historical trade routes, is based on Michalapoulos, Naghavi and Prarolo (2012).

The dependent variables for this study are taken from the WVS. I use a set of questions posed by the WVS to form a composite index representing ‘Gender Attitudes.’ To construct the composite index, I use the following indicators. The first asks respondents if “Women have the same rights as men.” This indicator is measured on a scale from 1 to 10 with 1 being, “Not an essential characteristic of democracy” and 10 being “An essential characteristic of democracy.” In the WVS, data is accumulated based on individual observations; to aggregate this to the desired unit of analysis, I take the mean of all individual observations for each country.

Next, I add alternative measures of gender attitude to the index. These are, “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women,” and, “If a woman earns more money than her husband, it’s almost certain to cause problems.” These indicators are measured from 1 to 3, with 1 being Agree, 2 being Neither, and 3 being Disagree. The next set of alternative measures I use to build the composite index are, “When a mother works for pay, the children suffer”, “On the whole, men make better political leaders than women do,” “A university education is more important for a boy than for a girl,” and “On the whole, men make better business executives than women do.” These indicators are measured from 1 to 4, with 1 being Strongly Agree, 2 being Agree, 3 being Disagree and 4 being Strongly Disagree. Finally, I include, “(How justifiable is it) for a man to beat his wife?” whereby the indicator is measured from 1 to 10, with 1 being Never Justifiable and 10 being Always Justifiable.

Note that, with the exception of “(How justifiable is it) for a mean to beat his wife”, for all the measures of gender attitude, the higher the number, the more gender equal the result. Hence, I augment these measures in three ways to form the composite index. First, I switch the scale of measurement for lattermost indicator – “(How justifiable is it) for a mean to beat his wife?” – such that a higher number represents a more gender equal perspective. Next, for the sake of consistency, I scale all measures to a scale from 1 to 10. Higher readings imply more gender equal attitudes. Finally, I take the average readings of the eight gender attitudes to be the composite index reading for overall ‘Gender Attitude.’ The distribution of gender attitudes by country is shown in Figure 1 below. A list of countries is provided in the Appendix.

For the composite index to be insightful, it is important for the various gender attitudes to be highly positively correlated with one another. If there was no correlation between one of the variables and all other variables, then that one variable may be removed from the composite index. If there was a consistent negative correlation between one of the variables and all other variables, then the composite index will, when regressed on the right-hand-side variables, lead to underestimations of the regression coefficient. I check for the cross-correlations of the variables, presented in Table 1 below. As we can see, there is strong positive correlation between all the indicators with one another, though the indicator, “It is unjustifiable for a man to beat his wife” is, on the whole, less correlated than the others. However, the correlations are still relatively strong and thus, the composite index on gender attitudes is reasonably representative of the separate gender attitude indicators.

Figure 1 – Distribution of Gender Attitudes by country, by quintile

Source: World Values Survey (2010-2014 Wave)

Table 1 – Cross-Correlation of Gender Attitude Indicators

Sources: World Values Survey, Author Calculations

Data for ‘Muslim-ness’ is taken from the Correlates of War (“COW”) Project. The Correlates of War Project was founded in 1963 by J. David Singer, a political scientist at the University of Michigan. The project’s purpose is to systemically accumulate scientific knowledge about war and does so by facilitating the collection, dissemination and use of accurate and reliable quantitative data in international relations. The unit analysis for all data in the Correlates of War Project is the ‘state’. Available data from the Correlates of War project includes The New COW War Data, 1816-2007, which provides a list of wars from 1816 to 2007, National Material Capabilities which gives six indicators that determine state power, Diplomatic Representation between countries from 1817 to 2005 and Bilateral Trade flows between states from 1870 to 2009, among others.

For the purposes of this paper, I take the Correlates of War project’s World Religion Data which provides detailed information about religious adherence worldwide, in 5-year intervals, from 1945 to 2010. The data records percentages of the state’s population that practice a given religion. Religions included in this data set are, among others, Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism and, even, Atheism. All data are collated from the respective nations’ statistical databases such as censuses, surveys, fact-books and so on. With this data, I define the degree of ‘Muslim-ness’ of a country as the historical 55-year average percentage of population that is Muslim. This definition is useful on several counts. Firstly, it allows for the ‘depth’ of historical Muslim-ness in a country which allows for greater variation across states and thus, better empirical estimates of gender attitudes as opposed to a simple binary configuration. Secondly, if culture, as defined by Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales (2006) as something that is transmitted from generation to generation, then taking the long-run ‘Muslim-ness’ of a country may proxy how more deeply-ingrained Islam is in the present culture of the given country. There is some caution on taking the mean percentage of the Muslim population especially with regards to countries with high variances, but it is unlikely that, except in the event of exodus and/or genocide, the proportion of Muslims in a country would have a high standard deviation. The long-term ‘Muslim-ness’ of nations is mapped in Figure 2 below.

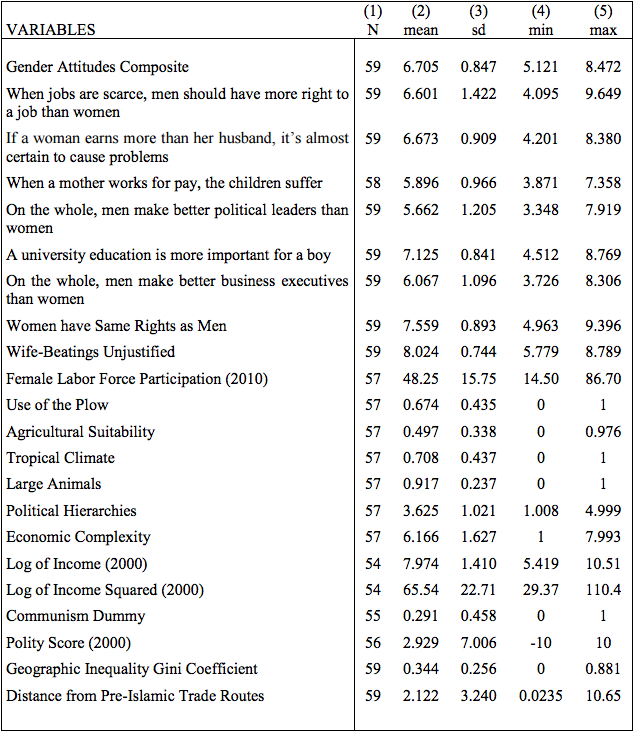

To avoid issues with omitted variable bias, I include a set of controls on gender attitudes. These controls are taken from Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013) where the authors employed historical controls and contemporary controls in their regressions alongside historical plough use, the primary right hand side variable. The historical controls they use are agricultural suitability, domesticated animals, tropics, political hierarchies and economic complexity, which the authors all argue may impact cultural norms on gender roles. Since they uncovered that historical plough use has an impact on gender preferences, I include historical plough use, by their definition, into the set of controls as well. The contemporary controls they use are log of income, the log of income squared, a communism indicator and polity scores. The data used by the authors for their contemporary controls – income and polity scores – are based on 2000 data. Descriptive statistics for the various variables are provided in Table 2 below.

Figure 2 – Distribution of Muslim-ness of nations across the world

Source: Correlates of War World Religion Data

Table 2 – Descriptive Statistics

Sources: World Values Survey (2010-2014 wave), Correlates of War, Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013), Michalapoulos, Naghavi and Prarolo (2012), Author calculations

With these 3 datasets, I specify my baseline OLS regressions as follows:-

GenderAttitudesi = α + βMuslimi + χjΧj + δiωi + ε (1)

The dependent variable, GenderAttitudesi, is the 1 to 10 rescaled indicator for the composite index, comprising the 8 measures of gender attitudes, for country i. Recall that a higher number implies a more gender equal attitude. The primary right hand side variable, Muslimi, denotes the degree of Muslim-ness of country i. Χ denotes the historical controls and contemporary controls for gender attitudes. ωi are continent dummies, as per Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013). ε is the error term. Therefore, if a culture of more deeply ingrained ‘Muslim-ness’ is associated with more gender unequal attitudes, we should see a negative coefficient on β. The opposite would be true if the degree of ‘Muslim-ness’ is associated with more gender equal attitudes.

The baseline specification is not without potential endogeneity issues. For one, there is always the possibility of omitted variable bias, particularly for unobservable characteristics without reasonable proxies. Consider, for instance, a preference for polygamy. This lends itself to correlation with ‘Muslim-ness’ (and Mormon-ism) and may also have an impact on overall gender attitudes. There is also the possibility of reverse causality. If a society is more gender unequal, individuals holding those norms and attitudes may seek a religion that they believe is more representative of their beliefs, and if they believe that Islam is such a religion, then gender attitudes could lead to the degree of ‘Muslim-ness’ which will bias the results.

To account for these issues, I undertake an Instrumental Variable (IV) regression where the first stage instruments are taken from Michalapoulos, Naghavi and Prarolo (2012). Their paper examines the spatial distribution of Muslim societies, attempting to shed light on the geographic origins of Muslim societies. Their empirical analysis was conducted across nations, ‘virtual nations’ and ethnicities and establishes that geographic inequality and proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes are key factors that explain present-day Muslim adherence.

The hypothesis that proximity to trade routes, even long-distance trade routes, was critical in the expansion of Islam is well-documented by prominent Islamic scholars; further references are available in Michalapoulos, Naghavi and Prarolo (2012). However, according to the authors, the tight relationship between geographic inequality and Muslim adherence is less well-known. They argue that a region that is characterized by unequal agricultural potential implies that there are few pockets of arable land where farming is feasible and a large share of dry regions where pastoralism is the most likely economic activity. These differences enable people living in those areas to specialize, which provided the basis for intra-regional trade. The next way in which unequal geography led to the expansion of Islam is the linkage between geographic inequality and social inequality and predation within a region. The authors point out that Ibn Khaldun, one of the most important philosophers in both the Muslim and world history, observed that a crucial factor for understanding Muslim history is “the central social conflict between the primitive Bedouin and the urban society.” Nomads posed a threat to lands which were highly arable for farming. To combat this, the authors argue that Islam provided a centralizing state-building force, featuring redistributive principles, which enabled order and relative peace in the region, thereby further facilitating trade and inducing Islamic culture.

The authors econometrically establish their claims via OLS regressions, with controls for continental dummies, log average land quality, distance to Mecca, absolute latitude, distance to the coast, average elevation and regional fixed effects. They conduct robustness checks via alternative specifications and pairwise correlations between variables. Given that the results hold, I apply their results to this study, using geographic inequality and proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes as instruments for the IV regression. I am grateful to Stelios Michalapolous for providing me with the relevant cross-country data from their study. The first stage regression regresses ‘Muslim’ on these instruments. The predicted ‘Muslim’ variables are then used in the second stage regression on which gender attitudes are regressed. The specification is as follows:-

First-Stage:

Muslimi = α + γGeogInequalityi + φiProxITRi + χjΧj + δiωi + ν (2)

Second-Stage:

GenderAttitudesi = α + βMuslimHati + χjXj + δiωi + ε (3)

GeogInequalityi and ProxITRi represent geographic inequality and proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes respectively for country i. Like equation (1), Χ represents the historical controls and contemporary controls for gender attitudes. ωi are continent-fixed effects. ε is the error term. In equation (3), MuslimHati is the predicted value of Muslim-ness for country i.

The exclusion restriction requires that geographic inequality and proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes impact gender attitudes in a given nation only via the nation’s degree of ‘Muslim-ness.’ The two instruments, as argued by Michalapolous, Naghavi and Prarolo (2012), largely lend themselves to a propensity to trade which made the relevant geographic areas more conducive to the spread of Islam. Moreover, geographic inequality also led to social inequality and predation that opened the doors to a centralizing state-building force such as Islam in establishing order and relative peace. On the other hand, it is plausible that greater trade and a greater need to protect regions from predation may lead to differences in gender roles in society – for instance, men as soldiers and women as homemakers or men as travelling traders and women as local goods traders – that may persist historically and impact gender attitudes today, which would violate the exclusion restriction.

I check for this in two ways. First, I run my preferred OLS specification with both geographic inequality and proximity to pre-Islamic trade routes included in the regression. If the variables are statistically significant, then they may directly impact gender attitudes today. Second, I test for the validity of the instruments via a standard IV over-identification test, given that I instrument for one endogenous variable – a nation’s ‘Muslim-ness’ – with two instruments. If the p-value of the test is not statistically significant, then I conclude that the instruments are valid.

As a robustness check, I use the individual definitions of gender attitudes – the ones used to form the composite index - based on the indicators from the World Values Survey that I mention above. The results are presented in Section III.

III. Results

Part 1 – OLS Specifications

I present the regression results from the OLS specification in Table 3. For the sake of brevity, I present only the relevant variables, combining all the historical and contemporary controls into their respective groups.

Table 3 – OLS Regressions of ‘Muslim-ness’ on Gender Attitudes

Note: Robust standard errors are denoted in parantheses. * denotes significance at the 5% level; ** denotes significance at the 1% level.

Sources: World Values Survey (2010-2014 wave), Correlates of War, Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013), Author calculations

In all five specifications, the degree of Muslim-ness of a country is associated with statistically significantly less equal gender attitudes. The baseline regression, regression 1, regresses the Gender Attitudes composite index on degree of ‘Muslim-ness.’ On average, a 10 percentage point increase in ‘Muslim-ness’ over the time period 1945 to 2010 is statistically significantly associated, at the 1% significance level, with a reduction in the gender attitude index of approximately 0.16 points. Put another way, the difference in gender attitudes that is attributable to the degree of ‘Muslim-ness’ between Turkey and the United States, for example, is about 1.6 points on a 10 point scale.

Regression 2 adds historical controls of Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013) to the specification without the contemporary controls. The magnitude of the coefficient on Muslim-ness is smaller than that in Regression 1 but it is still statistically significantly negative at the 1% level. Regression 3 adds the contemporary controls – income, income squared, polity score and a communism dummy. This has the effect of reducing the magnitude of the coefficient to 0.864, meaning that, on average, a 10 percentage point increase in ‘Muslim-ness’ of a country is associated with a reduction on the gender attitude index of approximately 0.09 points. The coefficient is still statistically significant at the 1% level. Regression 4 includes both historical controls and contemporary controls into the specification. Again, the sign and statistical significance of the ‘Muslim-ness’ coefficient is negative and significant at the 1% level.

In Regression 5, my preferred OLS specification, continent dummies are added to the specification. The reason continent dummies are used, as opposed to country dummies, is that there is high multi-collinearity between the countries. In this specification, a 10 percentage point increase in the Muslim-ness of a country is associated with, on average, a 0.07 point decrease in the gender attitude composite index, controlling for the historical and contemporary controls, and continent dummies. To make it more concrete, the difference in gender attitudes that is attributable to degree of ‘Muslim-ness’ of a society, on a 10 point scale, between Turkey and the United States is approximately 0.7 points, which is still fairly substantial in practical terms. The coefficient is statistically significant at the 1% level. Furthermore, the R-Squared of the regression is 0.82, indicating that the right-hand-side variables used in the specification explain more than three quarters of the variation of gender-attitudes across countries.

For robustness checks, Table 4 presents the OLS estimation of the relationship between ‘Muslim-ness’ and the individual indicators – scaled 1 to 10 – that make up the gender attitude composite index. There are 8 such indicators in all. I also include Female Labor Force Participation in 2010 – as per Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013) – as a robustness check. Thus, there are 9 specifications in all. In each of the 9 specifications, I include the historical controls, contemporary controls and continent dummies.

Table 4 – OLS Regressions with Alternative Dependent Variables

Note: Robust standard errors are denoted in parantheses. * denotes significance at the 5% level; ** denotes significance at the 1% level.

Sources: World Values Survey (2010-2014 wave), Correlates of War, Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013), Author calculations

On average, an increase in the ‘Muslim-ness’ of a country is associated with lower female labor force participation, a higher likelihood to hold the belief that men should have more right to a job than women when jobs are scarce, a higher likelihood to hold the belief that if a woman earns more money than her husband, it’s almost certain to cause problems, a higher likelihood to hold the belief that when a mother works for pay, the children suffer, a higher likelihood to hold the belief that, on the whole, men make better political leaders and business executives than women do and a higher likelihood to hold the belief that a university education is more important for a boy than a girl. With the exception of the lattermost dependent variable, all the coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% level and are all practically significant, magnitude-wise. However, the more Muslim a country is, the more likely it is to find it unjustifiable for a man to beat his wife. This coefficient is significant at the 5% level. It is also worth noting that there is a positive relationship between ‘Muslim-ness’ and the belief that women should have the same rights as men in a democracy. This effect is, however, not statistically significant.

Overall, a higher degree of ‘Muslim-ness’ of a nation is associated with more gender unequal attitudes both overall and at individual indicator levels, with the exception of women rights and wife-beating. Yet, these OLS regressions alone are not enough to establish causality; for reasons discussed earlier, they do not allow us to conclude that, on average, a higher degree of ‘Muslimness’ causes more gender unequal attitudes in a given nation. To overcome those biases and establish causality, thereby increasing the robustness of this analysis, I undertake Instrumental Variable regressions, using geographic inequality and distance from pre-Islamic trade routes as instruments.

Part II – Instrumental Variable Specifications

I present the primary regression results from the IV specifications in Table 5. For the sake of brevity, I present only the relevant variables, combining all the historical and contemporary controls into their respective groups. I also undertake the standard IV post-estimation tests of exogeneity, instrument strength and over-identification (since I use two instruments to instrument for one variable).

Table 5 – IV Regression Results of ‘Muslim-ness’ on Gender Attitudes

Note: Robust standard errors are denoted in parantheses. * denotes significance at the 5% level; ** denotes significance at the 1% level.

Sources: World Values Survey (2010-2014 wave), Correlates of War, Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013), Michalapoulos, Naghavi and Prarolo (2012), Author calculations

To perform a first check on the exclusion restriction, I regress the gender attitude composite index on ‘Muslim-ness’, historical controls, contemporary controls and continent dummies and the two instruments – Geographic Inequality and Proximity to pre-Islamic Trade Routes. I find that the coefficient on the instruments are not statistically significant and hence, they do not need to be specified in the OLS regression and may then be considered for use as valid instruments in the Two Stage Least Squares regression.

The IV(1) equation performs a two-stage least squares regression without the historical controls, contemporary controls and continent dummies. At the first stage, the Geographic Inequality and Distance from Pre-Islamic Trade Routes are statistically significantly associated with ‘Muslimness’ at the 1% level, with the predicted sign. At the second-stage, the estimation finds that ‘Muslim-ness’ does cause more gender unequal attitudes. An increase in the ‘Muslim-ness’ by 10 percentage points reduces the gender composite index score by approximately 1.8 points on a 10 point scale. The effect is statistically significant at the 1% level.

Given that I use two instruments to instrument for one right-hand-side variable, I conduct Wooldridge’s score test of over-identifying restrictions to test the validity of the instruments. Against the null hypothesis that both instruments are valid at the 5% level, the p-value is 0.06, indicating a failure to reject the null at the 5% level and so, the instruments are taken as valid. Next, I conduct an F-test of the instruments and find that the F-statistic of the instruments is 26.29. This is higher than the rule of thumb suggested by Stock, Wright and Yogo (2002) who suggest that the F statistic should exceed 10 for inference based on the 2SLS estimator to be reliable when there is one endogenous regressor and, as such, the instruments are strong. Finally, I conduct a test of exogeneity. The Wooldridge test and the regression-based test find a failure to reject the null that Islam is exogenous. This implies that, for this specification at least, OLS is a more efficient and a consistent estimator.

The IV(2) estimation performs a two-stage least square regression with the historical controls, contemporary controls and continent dummies. In the first stage, the signs for Geographic Inequality and Distance from Pre-Islamic Trade Routes are still as expected. However, the coefficient on Distance from Pre-Islamic Trade Routes is no longer statistically significant while the coefficient on Geographic Inequality is now only significant at the 5% level. In the secondstage, the statistical significance of the coefficient of ‘Muslim-ness’ disappears. While the sign is still the same, and the magnitude is roughly similar to the OLS estimate, it is no longer statistically significant.

I perform the same post-IV-estimation tests on IV(2). The instruments are still valid; the overidentification test yields a p-value of 0.27, thereby failing to reject the null of instrument validity. In terms of instrument strength, the F-statistic is still statistically significant at the 1% level, but is now reduced to 4.28. Finally, in the test on exogeneity, both the Wooldridge test and the regression-based test find a failure to reject the null that ‘Muslim-ness’ is exogenous. Thus, with the historical, contemporary and continent controls, the test on exogeneity finds that the OLS estimator is more efficient and is consistent and so, ‘Muslim-ness’ can be treated as an exogenous variable. Therefore, in selecting the result-of-choice in this paper, I take regression 5 from the OLS specifications in Table 3 to be reported.

For posterity, I also employed IV estimations on the individual indicators of gender attitudes and female labor force participation. In each of the regressions, I included the contemporary controls, historical controls and continent dummies. The results are presented in Table 6 below, side-byside with the OLS estimates shown in Table 4.

For all dependent variables, the signs are the same in both the OLS specification and the IV specification. However, the coefficient on ‘Muslim-ness’ is now statistically significant only for Female Labor Force Participation in 2010 and for the indicator, “When a mother works for pay, the children suffer.” In both cases, the magnitude of the coefficient has also increased by a substantial amount. From these individual attitude specifications, given that the ‘Muslim-ness’ of a society has no effect on 7 out of the 8 characteristics that comprise the gender attitudes composite index, it is easy to see why ‘Muslim-ness’ has no statistically significant impact on the gender attitude composite index.

On the whole, the instruments are valid and are relatively strong. However, tests of exogeneity indicate that ‘Muslim-ness’ can be treated as an exogenous variable and, consequently, the OLS estimator is an efficient and consistent estimator of the relationship between ‘Muslim-ness’ and gender attitudes. Therefore, I draw on the OLS estimates as the primary results of this paper and find that, on average, an increase in the ‘Muslim-ness’ of a society causes a statistically significantly negative impact on gender attitudes for a given country controlling for historical and contemporary controls and continent dummies.

Table 6 – IV and OLS Estimations with Alternative Dependent Variable

Note: Robust standard errors are denoted in parantheses. * denotes significance at the 5% level; ** denotes significance at the 1% level.

Sources: World Values Survey (2010-2014 wave), Correlates of War, Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn (2013), Michalapoulos, Naghavi and Prarolo (2012), Author calculations

IV. Implications and Policy Recommendations

From a normative perspective, gender equality is an important cause to strive towards. However, if a society’s ‘Muslim-ness’ is an important factor in contributing to gender inequality, how then should we move forward in terms of eliminating gender inequality? It would not be politically feasible nor constitutional for countries to introduce a policy that bans the Islam religion. Further, as Campante and Yanagizawa-Drott (2014) point out, Islam does lead to higher measures of subjective well-being – happiness and meaning – for individuals. Thus, the imperative for policy is to design policies that promote gender equality more heavily in Muslim societies that will lead to the dissipation of gender unequal attitudes over time, while preserving the many benefits that a Muslim society may bring its citizens.

Perhaps a helpful starting place is work by Beaman et al (2009) who exploit a random assignment of gender quotas for female leadership villages across Indian villages to investigate whether having a female chief councilor affects public opinion towards female leaders. In particular, the authors are able to investigate implicit biases against women via the use of survey and experimental data that measures voters’ taste for female leaders and their perceptions of gender roles and female leaders’ effectiveness via Implicit Association Tests. They find that while exposure to a female leader does not alter villagers’ taste preference for male leaders, it does weaken stereotypes about public and domestic gender roles and eliminate the negative bias against female leaders’ effectiveness as perceived by male villagers. Furthermore, the authors find that the changes in implicit biases are electorally meaningful; after 10 years of the quota policy, women are more likely to contest and win seats in villages that have been continuously required to have a female leader.

Other such ‘quota’ policies have also been introduced around the world, to mixed results. Malaysia, for example, introduced a policy that required 30% of corporate boards be comprised of women. Such a policy was also introduced in Norway where, in 2003, it passed a law requiring at least 40% representation of each gender on the board of publicly limited liability companies. Bertrand et al (2014) document that while this reform had a positive direct effect on the newly appointed female board members, such as better qualified female board members than their predecessors and a reduction in the gender gap in earnings within boards, there is no evidence that those benefits trickled-down even to highly qualified women whose qualifications mirror those of board members but were not appointed to boards. They also find little evidence to suggest that the reform impacted the decisions of women more generally; the policy was not accompanied by any change in female enrollment in business education programs, or a convergence in earning trajectories between business school male and female graduates.

At the household level, a potential policy tool would be to introduce financial incentives for parents to invest in or have girls. For instance, Schultz (2004) reports that conditional cash transfer programs such as Progresa or Oportunidades in Mexico provide a larger financial transfer to families to educate girls than boys, in large part to narrow the dropout rate gap between boys and girls. Another method, suggested by Jayachandran (2014), would be to shift household financial resources to mothers from fathers; for instance, social assistance could be paid to the mother instead of the father. Indeed, Duflo (2003) provides evidence that when women control a larger share of household income, girls’ outcomes improve.

In the classroom, using a dataset of over 30,000 observations on students in Milan, Italy, Anelli and Peri (2013) find that individuals assigned to a high school class with a larger proportion of students of the same gender were more likely to choose high-earning university majors, which then led to higher paying jobs. They argue that the channel through which this effect works is higher self-confidence for girls who, ex ante on average, tend to choose lower earning university majors. When girls derive more confidence from fellow female students, perhaps feeling more comfortable speaking up in front of just females, they may decide to pursue higher-earning and more historically male-dominated university majors. In Sierra Leone, Mocan and Cannonier (2012) find evidence that an exogenous education policy reform in 2011 led to an increase in schooling for women which improved women’s attitudes towards matters that impact women’s health and on attitudes regarding violence against women. However, they also find that increased schooling for men had no impact on men’s attitudes towards women’s well-being.

More generally, the fact that more Muslim societies are also more strongly associated with having more gender unequal attitudes means that efforts to close the gender gap in all segments of society are even more difficult in more Muslim societies. This therefore requires more intense and committed policy focus, as pointed out by Duflo (2012) who argues that “continuous policy commitment to equality for its own sake may be needed to bring about equality between men and women.” Against this backdrop, it is imperative for policymakers in Muslim societies to push for a wide range of policy prescriptions to ensure that the gender gap in their respective societies narrows over time, counteracting the result of a historical persistence of ‘Muslim-ness’ in their societies on gender attitudes.

I analyze the impact of the ‘Muslim-ness’ of a society, over the past 65 years, on gender attitudes today. Specifically, I find a, on average, statistically significantly negative relationship between the ‘Muslim-ness’ of a society and gender attitudes, controlling for historical controls, contemporary controls and continent dummies. In my preferred specification, a 10 percentage point increase in the Muslim-ness of a country is associated with, on average, a 0.07 point decrease in the gender attitude composite index. To make it more concrete, the difference in gender attitudes attributable to the degree of ‘Muslim-ness’ in society, on a 10 point scale, between Turkey and the United States is approximately 0.7 points, which is fairly substantial in practical terms.

To provide against potential endogeneity issues, I instrument for the ‘Muslim-ness’ of a society using Geographic Inequality and Distance from Pre-Islamic Trade Routes which are taken from work by Michalopoulos, Naghavi and Prarolo (2012). However, exogeneity tests of the primary regressor of interest finds that ‘Muslim-ness’ is exogenous to gender attitudes and hence, the OLS estimate is both efficient and consistent, and taken to be the primary result.

Given that a more Muslim society is likely to have more gender unequal attitudes, much policy work needs to be done to reduce the gender gap between males and females in such societies. I have provided a snapshot of possible policies but such policies should certainly not be implemented blindly, over concerns of external validity, but rather, be contextualized to fit the relevant setting for a given society. Further, it will not be adequate to simply depend on economic development for the narrowing of gender equality; a continuous push for policies to commit to equality for its own sake may be necessary.

Moving forward, the avenue for future research is two-fold. First, from a technical perspective, it would be helpful to have more disaggregated data, perhaps at a within-country sample. For instance, one could compare how gender attitudes among Chinese and Malays1 in Malaysia to eliminate country-fixed effects which may bias the more aggregated results. Furthermore, better measures of ‘Muslim-ness’ would be appropriate; in particular, it would be useful to have survey data on actual practice of the Muslim religion as opposed to simply stating the reported proportion of Muslims for a given country. Societies with a smaller proportion of Muslims that devoutly practice Islam are likely to be qualitatively more Muslim than societies with a larger proportion of Muslims who are not devout. Second, having identified that more Muslim societies are likely to have more unequal gender attitudes, the next step would be to identify the particular channels through which unequal gender attitudes arise in Muslim societies. This, I believe, is a very promising avenue for future research and will provide a solid starting platform for policy work to improve on the gender gaps in Muslim societies.

Footnote

1 In Malaysia, all Malays are Muslims whereas the vast majority of Chinese are non-Muslim. We could also do a comparison between non-Muslim Chinese and Muslim Chinese but the sample size for Muslim Chinese may be very limited.

Appendix

List of Countries in the Study

Algeria

Argentina

Armenia

Australia

Azerbaijan

Bahrain

Belarus

Brazil

Chile

China

Colombia

Cyprus

Ecuador

Egypt, Arab Rep.

Estonia

Germany

Ghana

Hong Kong

India

Spain

Iraq

Japan

Jordan

Kazakhstan

Kuwait

Kyrgyzstan

Lebanon

Libya

Malaysia

Mexico

Morocco

Netherlands

New Zealand

Nigeria

Pakistan

Peru

Philippines

Poland

South Korea

Qatar

Romania

Russia

Rwanda

Slovenia

South Africa

Sweden

Taiwan

Thailand

Trinidad and Tobago

Tunisia

Ukraine

United States

Uruguay

Uzbekistan

Yemen, Rep.

Zimbabwe

References

Albanesi, S., and C. Olivetti. (2007). “Gender Roles and Technological Progress.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 13179.

Alesina, A., and E. La Ferrara. (2005). “Preferences for Redistribution in the Land of Opportunities.” Journal of Public Economics, 89, pp. 897-931.

Alesina, A., and Giuliano, P. (2010). “The Power of the Family.” Journal of Economic Growth, 15, pp. 93-125.

Alesina, A., and N. Fuchs-Schuendeln. (2007). “Good Bye Lenin (or not?) – The Effects of Communism on People’s Preferences.” American Economic Review, 97, pp. 1507-1528.

Alesina, A., Giuliano, P., and N. Nunn. (2013). “On the Origin of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 128(2), pp. 469-530.

Anelli, M., and Peri, G. (2013). “The Long Run Effects of High-School Class Gender Composition.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 18744.

Bailey, M. J. (2006). “More Power to the Pill: The Impact of Contraceptive Freedom on Women’s Life Cycle Labor Supply.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(1), pp. 289-320.

Barro, R., and R. M. McCleary (2006). “Religion and Economy.” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2), pp. 49-72.

Barro, R., and R.M. McLeary (2003). “Religion and Economic Growth across Countries.” American Sociological Review, 68(1).

Beaman, L., Chattopadhyay, R., Duflo, E., Pande, R., and Topalova, P. (2009). “Powerful Women: Does Exposure Reduce Bias?” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(4), pp. 1497-1540.

Becker, S.O., and L. Woessmann. (2009). “Was Weber Wrong? A Human Capital Theory of Protestant Economic History.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(2), pp. 531-596.

Benabou, R., and Tirole, J. (2006). “Belief in a Just World and Redistributive Politics.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(2), pp. 6990746.

Bertrand, M., Black, S.E., Jensen, S., and Lleras-Muney, A. (2014). “Breaking the Glass Ceiling? The Effect of Board Quotas on Female Labor Market Outcomes in Norway.” NBER Working Paper, No. 20256.

Bisin, A., and T. Verdier. (2000). “Beyond the Melting Pot: Cultural Transmission, Marriage, and the Evolution of Ethnic and Religious Traits.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), pp. 955-988.

Campante, F., and D, Yanagizawa-Drott. (2014). “Does Religion Affect Economic Growth and Happiness? Evidence from Ramadan.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, forthcoming.

Duflo, E. (2003). “Grandmothers and Granddaughters: Old Age Pension and Intra-Household Allocation in South Africa.” World Bank Economic Review, 17.

Duflo, E. (2012). “Women’s Empowerment and Economic Development.” Journal of Economic Literature, 50(4), pp. 1051-1079.

Fernandez, R. (2007). “Women, Work and Culture.” Journal of the European Economic Association, 5(2-3), pp. 305-332.

Fernandez, R., and A. Fogli. (2009). “Culture: An Empirical Investigation of Beliefs, Work, and Fertility.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 1(1), pp. 146-177.

Fortin, N. (2005). “Gender Role Attitudes and the Labour Market Outcomes of Women across OECD Countries.” Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 21, pp. 416-438.

Ghazal Read, J. (2003). “The Sources of Gender Role Attitudes among Christian and Muslim Arab-American Women.” Sociology of Religion, 64(2), pp. 207-222.

Giuliano, P. and N. Nunn. (2013). “The Transmission of Democracy: From the Village the the Nation-State.” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 103(3), pp. 86-92.

Goldin, C. (2006). “The Quiet Revolution that Transformed Women’s Employment Education and Family.” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 96(2), pp. 1-23.

Grief, A. (2006). Institutions and the Path to Modern Economy: Lessons from Medieval Trade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., and L. Zingales. (2003). “People’s Opium? Religion and Economic Attitudes.” Journal of Monetary Economics, 50(1), pp. 225-282.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., and L. Zingales. (2006). “Does Culture Affect Economic Outcomes?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2), pp. 23-48.

Jayachandran, S. (2014). “The Roots of Gender Inequality in Developing Countries.” NBER Working Paper, No. 20380.

La Porta, R., De Silanes, F.L., Shleifer, A., and R. Vishny. (1997). “Legal Determinants of External Finance.” Journal of Finance, 52(3), pp. 1131-1150.

Maoz, Z., and E. A. Henderson. “The World Religion Dataset, 1945-2010: Logica, Estimates and Trends.” International Interactions, 39(3), in Correlates of War project.

Mocan, N. and Cannonier, C. (2012). “Empowering Women Through Education: Evidence from Sierra Leone.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 18016.

Michalopoulos, S., Naghavi, A., and Prarolo, G. (2012). “Trade and Geography in the Origins and Spread of Islam.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 18438.

Morgan, M. (1987). “The Impact of Religion on Gender-Role Attitudes.” Psychology of Women Quarterly, 11, pp. 301-310.

N. Nunn (2012). “Culture and the Historical Process.” Economic History of Developing Regions. 2;27(S1), pp. 108-126.

Nunn, N. (2008). “The Long Term Effects of Africa’s Slave Trades.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(1), pp. 139-176.

Nunn, N. (2009). “The Importance of History for Economic Development.” Annual Review of Economics, 1(1), pp. 65-92.

Ross, M. L. (2008). “Oil, Islam and Women.” American Political Science Review, 102(1), pp. 107-123.

Schultz, T. P. (2004). “School Subsidies for the Poor: Evaluating the Mexican Progresa Poverty Program.” Journal of Development Economics, 74, pp. 199-250.

Stock, J.H., Wright, J.H., and Yogo, M. (2002). “A survey of weak instruments and weak identification in generalized method of moments.” Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 20, pp. 518-529.

Tabellini, G. (2008). “The Scope of Cooperation: Values and Incentives.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(3), pp. 905-950.

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2013) Highlights of Women’s Earnings in 2012. United States: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Weber, Max. (1905) [2001]. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. London: Routledge Classic.