Co-authored with Dr Nungsari Radhi

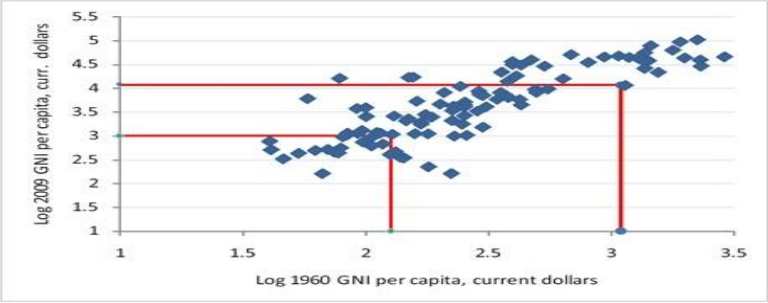

The economic reform agenda currently underway in Malaysia is a recognition that the prevailing economic model that has brought the country to a middle income status will not be able to take us further - to join the ranks of high income economies. Yet, Malaysia’s transformation must go beyond projects and policies – it must embrace the technological super-cycles that shape global economic history. To do so, Malaysia must not only entwine itself in the spirit of innovation but also diffuse the benefits of that innovation as pervasively as possible. Only by doing both will Malaysia make a serious drive towards a developed, high-income economy. Very few countries have made the jump from middle-income to high-income. World Bank economist Ivailo Izorvski finds that of the countries that were middle-income in 1960, almost three-fourths remained middle-income or regressed to low-income by 2009. The chart below illustrates this observation. The red lines show the middle income threshold and the high-income threshold in both 1960 and 2009. For a country to jump from the middle-income level to the high-income level, it has to be to the left of the outer red line (below high-income in 1960) and above the outer red line (above high income in 2009).

Chart 1: Transition from middle-income to high-income, 1960-2009

Source: Izovrsky (2011)

Of the countries which were middle-income in 1960, very few crossed over into highincome territory in 2009. Most countries remained middle-income or, at the most, became upper middle-income. Thus, if we merely do the same things and even doing them better, it is more likely that Malaysia continues moving higher within the middleincome group without actually jumping into the high-income group. Improving without significant structural change will still keep the economy on the same trajectory, albeit on a steeper curve, but it will not result in a discontinuous jump to a higher-level trajectory. Economies that cannot find that discontinuity stay on the same path. If we consider countries that have made the jump, a common pattern emerges. South Korea made its jump through pursuing heavy industries before other countries in the region, save Japan. Taiwan attained its jump by hopping on the emerging electronics industry. Singapore exploited its location as a go-between between Japan and the Middle East as well as being open to the concept of importing high-skilled foreign talent. It moved away from its colonial logic of a port serving a regional hinterland. The commonality between these three countries is the willingness to be innovative by pursuing a new industry that latches on a global trend and from this willingness, the ability to diffuse this innovation as widely as possible. Diffusion of innovation means spreading the benefits of innovation economy-wide or removing barriers to the expansion of innovation. Innovation by itself or diffusion by itself is a necessary but insufficient condition to obtain a discontinuous jump. Consider the historical paths taken by dominant economic players throughout history. The narrative of economically dominant nations has been a tapestry of diverse circumstances. The economic landscape today is unrecognizable from the economic landscape of 500 years ago. We can view the changing landscape of economic history as a series of ‘Supercycles’, where a ‘Supercycle’ is an extended period of time encompassing many business cycles in the growth of a market or trend. In 2010, International Monetary Fund (IMF) figures show that the United States and the European Union contributed approximately 49% of world GDP. Thanks to economic historian Angus Maddison’s work, we can estimate that the share of the United States and Western Europe’s GDP to world GDP in the year 1500 was approximately 17%. If the global economic powers of today contributed less than one-fifth of global GDP roughly 500 years ago, who then were the drivers of the world’s economy? Maddison’s data finds that, in the year 1500, the contribution of China and India to global GDP was estimated to be a massive 49%. Yet, in the year 2010, this figure was a mere 12%, according to the IMF. However, global growth is now increasingly being re-driven by both China and India. China has even emerged as the second largest economy in the world. The economic expansion of the two nations has gained steam over the past decade, and looks set to continue apace well into the future. Thus, along the ‘Supercycle’ of global economic dominance, the world is trending towards a return of China and India as the world’s economic leaders. Of course, ‘Supercycles’ are not deterministic. It is not necessarily true that only China or India can emerge as global economic powers. Any country or region can stake its claim to be a dominant economic power in this new ‘Supercycle’. To do so, that nation or region must capitalize on cutting-edge technological advances that crop up throughout the globe. The contention here is that these ‘supercycles’ that produce economic superpowers are built around some technological shifts and the innovations around it. The mapping of technological ‘Supercycles’ first undertaken by Russian economist Nikolai Kondratiev in 1925 correctly predicted the future rise of petrochemicals, automobiles and information technology. His proposed cycles must be updated to reflect everything that happened after 1925. These cycles have been updated by academics to be:- 1771-1828: The Industrial Revolution 1829-1874: The Age of Steam and Railways 1875-1907: The Age of Steel and Heavy Engineering 1908-1970: The Age of Oil, Electricity, the Automobile and Mass Production 1971 onwards: The Age of Information and Telecommunications Plotting these cycles onto the ‘Supercycles’ of the global economy yields several fascinating trends. Firstly, while China reached its peak during the Industrial Revolution, it also began to decline during this cycle, with Western Europe and the United States rising. Secondly, as the United States and Western Europe exploited the benefits of the steam engine and railways to power the development of agricultural and manufacturing industries, China and India were declining at a rapid rate. While Western Europe peaked in the Age of Steel and Heavy Engineering, it began to decline in the Age of Oil, Electricity, the Automobile and Mass Production. The United States, however, continued its ascendancy with the automobile, mass production and consumption. The prominence of China and India, however, continued to decline across these two cycles. Finally, in the Age of Information and Telecommunications, the contributions of the United States and Western Europe have declined, while China and India are rising again.

Chart 2: Overlapping the Global Economic ‘Supercycle’ and the Technological “Supercycles’

Source: Angus Maddison, Nikolai Kondratiev

Two key questions emerge. What happened to China and India from 1771 to 1970? And how did the United States and Western Europe emerge to global dominance across the same time periods up till today? In China, the Qing Emperor pursued an isolationist trade policy, discouraging and prohibiting foreign trade until 1864. This policy, coupled with frequent civil wars as the Qing dynasty attempted to crush all Ming royalists only served to devastate the Chinese economy. The Chinese then engaged in the Opium Wars with the British who had superior arms and war machines and thus began a pattern of war, defeat, concessions, and silver payments to foreign powers. Hence, Chinese were rendered impotent at diffusing any innovations they may have crafted or gained from foreign sources, subsequently losing their spot as a global economic power. In India, the decline of its economic prominence began around the year 1700. The rise of India prior to that was due to the majesty of the Mughal Empire which, at its zenith, covered some 1.25 million square miles with more than 150 million subjects. After the death of Aurangzeb, the Mughal ruler, in 1707, the Mughal empire crumbled following attacks by the Maratha empire and the Safavids of Persia, the rise of Sikhism in the Punjab and eventually, British colonialism. India was never united enough to seize on the technological cycles that was pervasive in the West and may have even been restricted access by the British until India’s independence in 1947. In other words, India never stood a chance to innovate or even to diffuse the innovations of other parties into their nation. The United States and Western Europe achieved their ascendancy by embracing these technological cycles, building their economies through rapid industrialization in the 1800s and early 1900s. Despite facing the Revolutions of 1848, civil wars as well as 2 World Wars, these nations managed to maintain their global economic strength, buoyed by the increases in productivity and efficiency of technological advances. Unlike China and India, they seized on the innovations in technology and with the help of the railroad and the steam engine, managed to diffuse their technology throughout their regions. Putting it all together, the rise of the United States and Western Europe in the previous global economic ‘Supercycle’ coincided with the various technological ‘Supercycles’. By capitalizing on these technological ‘Supercycles’ and then diffusing these technologies, they were able to take pole positions in the global economy ahead of China and India whose prominence on the global stage fell as they failed to embrace those very same ‘Supercycles.’ As the world stands now at an inflection point, what then does this mean for Malaysia? We know that in the last 500 years, we were not in control of our own destiny 90% of the time. For the next 500 years, Malaysia is in a position to manifest its own destiny all on our own. It can chart its own way along the next ‘Supercycle’, focusing on making that discontinuous jump to a high-income nation. Perhaps the economic structure has not sufficiently divorced itself from the past colonial economy. However, history has shown that making the jump requires both innovation and the diffusion of innovation. On the bright side, the opportunity for diffusion is even greater today – markets are no longer merely national or inter-continental, markets are global. Any capable economy can leverage on global reach and resources for national advantage. The government can help in the diffusion of innovation. The diffusion of innovation is deterministic in the sense that the right set of policies, be it labour market policies, quality institutions and so on, will help to unlock new markets for the diffusion of innovation. However, this will only help place Malaysia on a steeper slope on the journey to a high-income nation; it will not help Malaysia make a discontinuous jump. What will complement the diffusion to drive the ‘jump’ is pure innovation. Unlike the diffusion of innovation, innovation is oftentimes stochastic. Innovation comes seemingly at random, an inter-play of demand for solutions, supply of knowledge and risk-taking behavior. An ‘innovative’ society is not one that is technologically-savvy – it is one that is culturally more open to risk-taking or failure. In Malaysia, a common trend is that we are too concerned in seeking success that we become too afraid of failure. Without a risk-taking and failure-accommodating cultural or societal attitude, we can never be an innovative society, without which, we will not be able to ride on any emerging supercycle or diffuse its benefits economy-wide. We will not find our discontinuous jump and remain on the same trajectory.